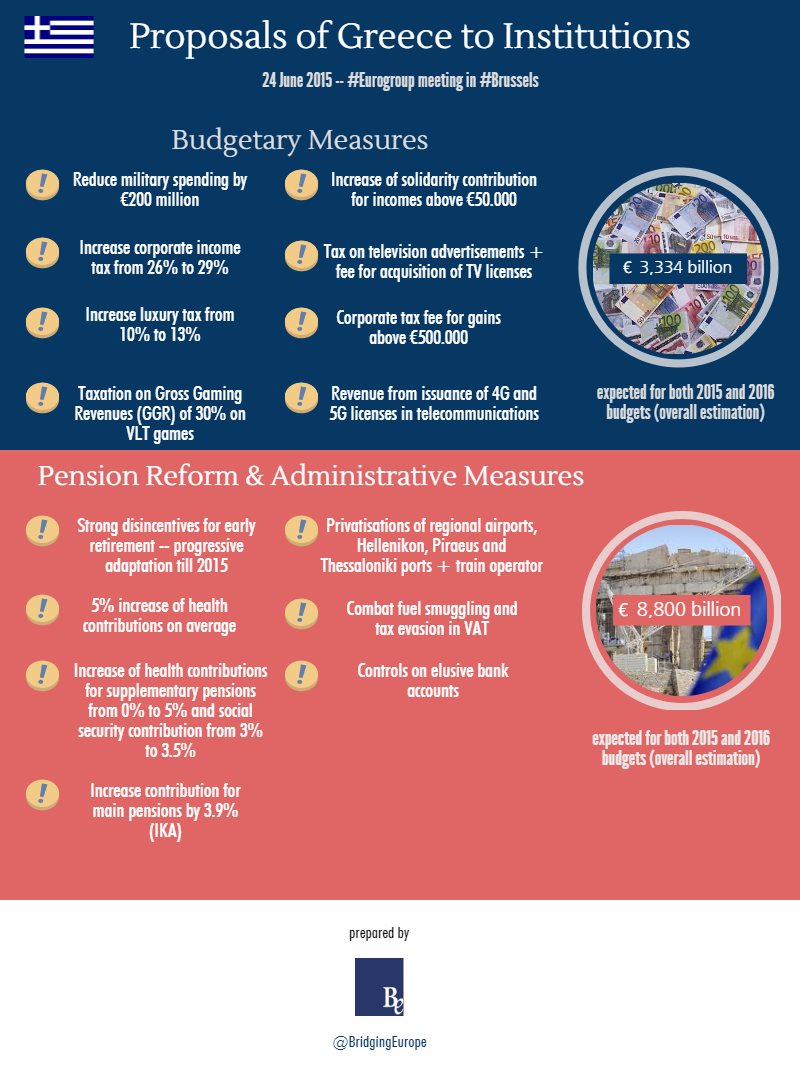

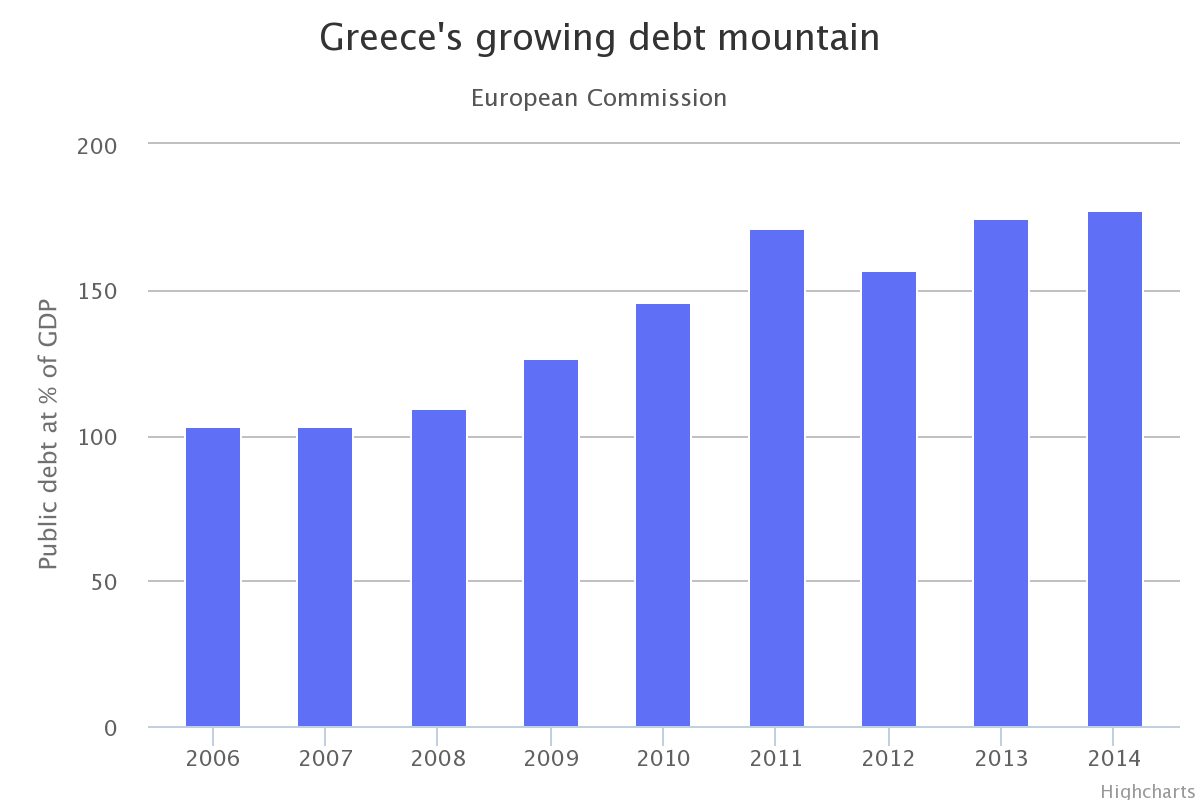

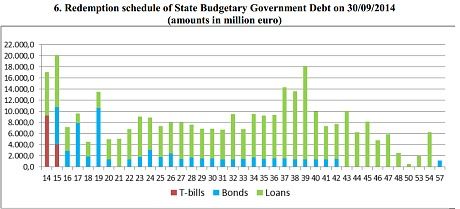

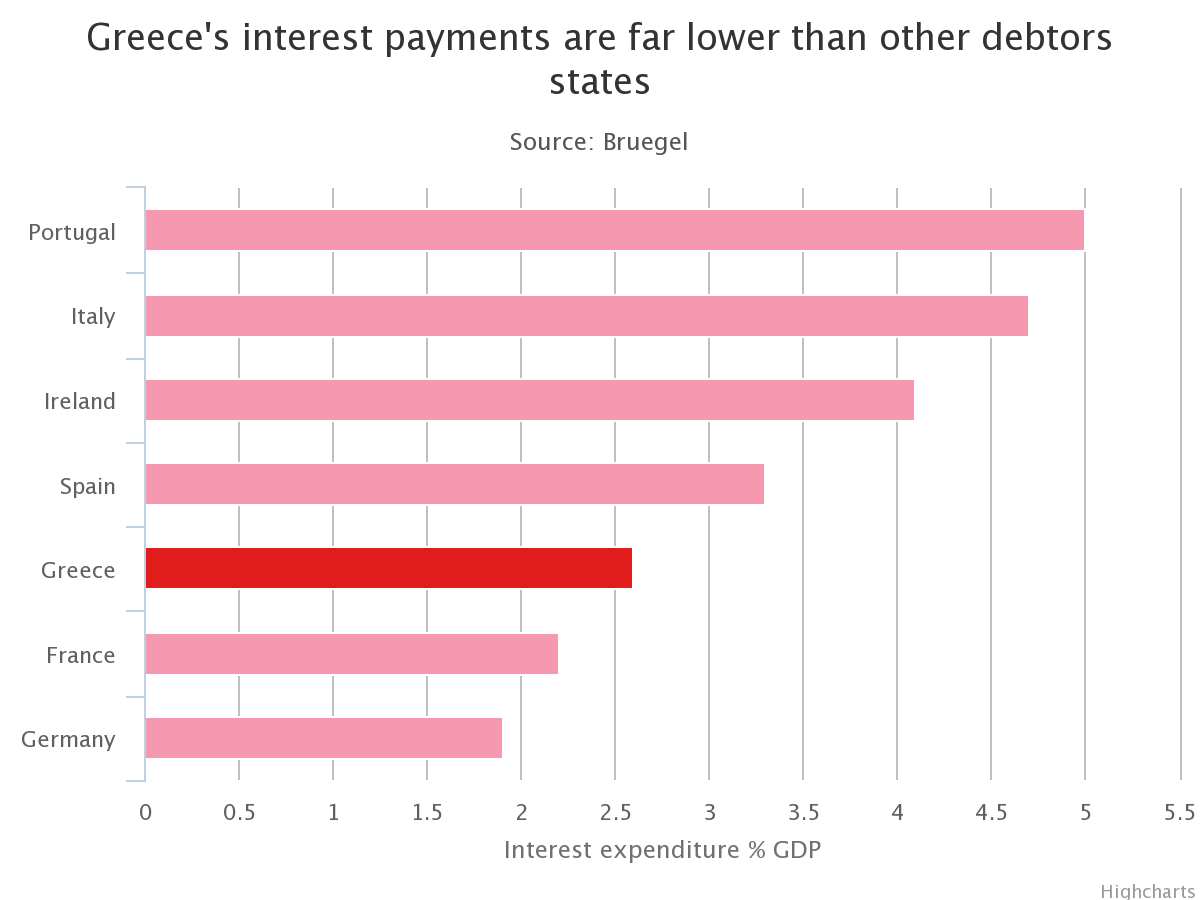

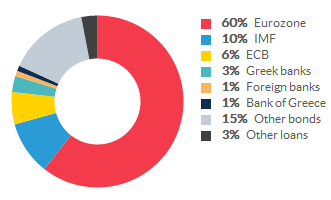

But the country’s economic crisis, which began at the end of 2009 when the world belatedly realized that Greece’s fiscal and trade deficits were unsustainable, is far from over; in fact it has taken a new and dangerous turn. The specter of a default on Greece’s sovereign debt — close to $500 billion, most of it owed to other Europeans — is haunting bankers and politicians. It could set off domino effects in the euro zone and beyond. Without urgent domestic reform and help from its European partners, Greece, a country of only 11 million people, risks being caught in an unbreakable cycle of decline. The bailout by the European Union, with the participation of the International Monetary Fund, comes with strict conditions attached, conditions that the government has only partially met so far. The government has reduced the budget deficit to 10.5 percent of Greece’s gross domestic product from more than 15 percent — no small achievement — and passed a bold pension reform plan. But it has been much more hesitant about structural reform of the economy and privatization of state-controlled enterprises, because of organized opposition by vested interests, resistance from within the party and from trade unions, and the snail’s pace of Greek bureaucracy. With unemployment at 16 percent, Greeks have been taking to the streets in protest against unpopular measures and a political system at risk of losing its legitimacy. Populists are having a field day, offering simplistic solutions and seeking scapegoats, preferably those beyond the nation’s borders. This is certainly not a phenomenon confined to Greece. Mr. Papandreou has reshuffled his cabinet and tried to appease his party members, while putting out feelers to the main center-right opposition party over the creation of a national unity government — so far, unsuccessfully. He has been undoubtedly weakened in the process. Greece desperately needs a radical renewal of its political class; at stake is the survival of many members of that establishment. It also needs a peaceful revolution in its economy and society. But democracy takes time. The next parliamentary elections may not be very far off, but the political and economic climate has to improve first. A few bold measures would send the message that the government is serious about scaling down the public sector. The solution is not more taxes to pay for poor quality services and over-staffed state organizations, the result of years of clientele politics in which the party in power appointed its friends to taxpayer-financed jobs. Greece needs more effective tax collection, together with the provision of a safety net for the rising numbers of the economically vulnerable. But economic measures are surely not enough; in drama, as ancient Greeks knew, you need catharsis. In today’s Greece, this means that people who have mismanaged public funds should be brought to justice. Neither of the main political parties has been enthusiastic about this, because they fear the unpleasant surprises from opening such a Pandora’s box. The creation of a national unity government, with a specific program of limited duration, would help to restore public confidence and broaden support for politically difficult measures, notably the elimination of public sector jobs. For the heavily indebted and uncompetitive economies of the European periphery, fiscal consolidation and structural reform — the mantras of I.M.F. economists — are a must. But what is the right dose of austerity? Too much could be economically counterproductive. Public tolerance of austerity may be reaching the breaking point. Growth is the key: without it, any adjustment program is doomed to fail. In trying to cut bureaucratic tape, Greek politicians will need to create an environment that is propitious to investment, which has not been the case for many years. European funds for investment could bolster the determination of local politicians to proceed with structural reform. Some in Europe are already talking about a new Marshall Plan for financially embattled countries. Solidarity with strings attached is a politically intelligent form of investment. The sovereign debt problem in several European countries, including Greece, raises the question of who should pay for the accumulated mistakes of the past — taxpayers or private creditors — and how much of the burden each country should bear. We need a political agreement on these questions, instead of piecemeal measures that leave politicians two steps behind the bond markets. Greece is at a dangerous crossroads. Other countries — Portugal, Ireland, maybe Spain — are coming behind it. The consequences of excessive borrowing and consumption, of the bursting of the credit bubble, have caught up with us. If we fail to deal with them effectively, the achievements of decades of increasing integration and shared sovereignty in postwar Europe may no longer be taken for granted.

The modern Greek state was established in 1830, following a victorious uprising against Ottoman rule. Two political issues are at stake (disputes with the Turkish - Cypriot political entity and with the Republic of North Macedonia because of view on history and associated recognition). Greece is a developed country and there is a very high Human Development Index (22nd highest in the world as of 2010). Greece has been a member of what is now the European Union since 1981 and the eurozone since 2001, NATO since 1952, and the European Space Agency since 2005. It is also a founding member of the United Nations, the OECD, and the Black Sea Economic Cooperation Organization. Greek spirits contributed the ideas of freedom, truth and beauty. In ancient Greece choruses performed for entertainment, celebration and spiritual reasons. Athens is the capital and the largest city in the country (its metropolitan area includes also Piraeus). There are solid trainings at first-class universities, breathtaking nature. Labour market, however is screened. Due to this, brain-drain is an underlying tragedy. |